cphfw and its discursive closure

iced vanilla #12 on how branding creates value by silencing contradictions

copenhagen fashion week (CPHFW) has successfully branded itself as the progressive, sustainable, and distinctly nordic alternative to the global fashion capitals. its official discourse highlights sustainability commitments, inclusivity, and creativity, projecting an image of a fashion event that not only sets trends but also sets standards for the industry.

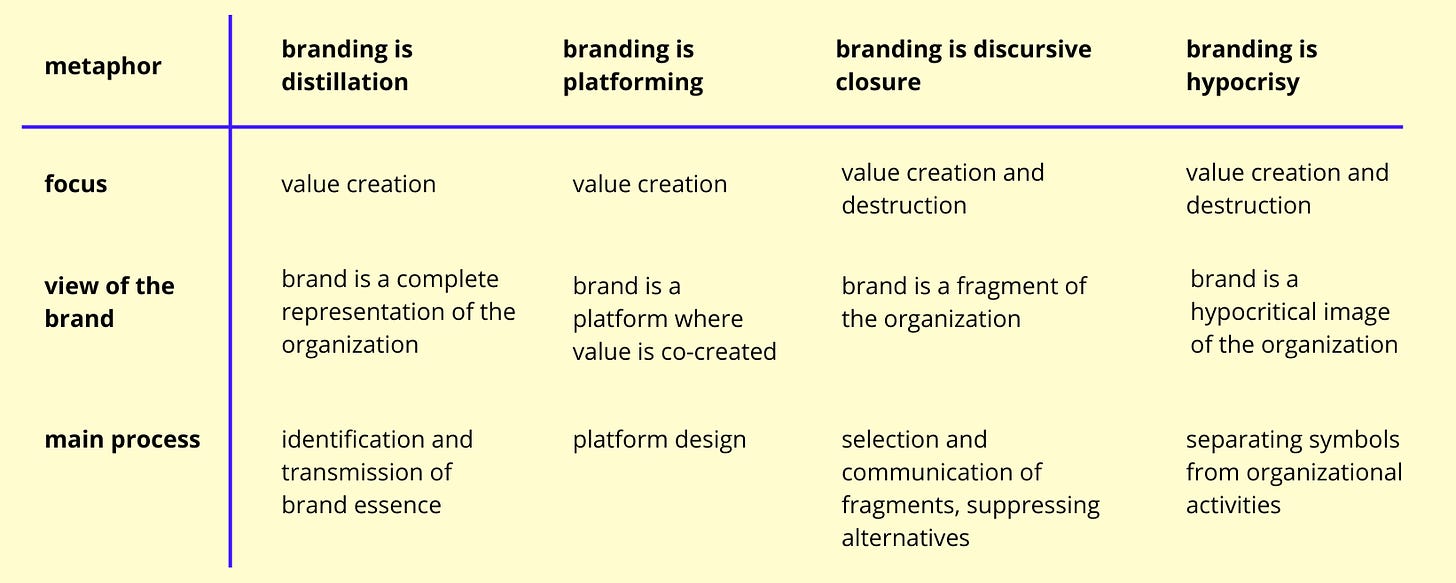

one of my master’s professors, jon bertilsson, together with jens rennstam, developed a framework that helps us understand this process differently. in their paper the destructive side of branding (2018), they argue that branding can function as discursive closure: instead of being a transparent reflection of reality, branding selects a strategic fragment to present as the “whole.” in other words, certain narratives are amplified - like “the world’s most sustainable fashion week” - while others are silenced.

for example:

sustainability is heavily promoted, yet several sponsors and participating brands rely on business models that directly contradict this narrative.

inclusivity is celebrated in language and selected campaigns, but questions of body diversity, racial representation, and class access remain largely unresolved.

cultural identity is framed around nordic coolness, but this tends to flatten the complexities of the social realities into a marketable aesthetic.

branding, at its core, is a managerial technique to manage the meaning and values associated with an organization, its products, or its activities. traditionally, it’s been understood as a value-creation tool: a way to establish positive associations that foster trust, signal quality, and simplify consumer choices. from a sociological perspective, branding doesn’t just sell products, it sells identities. it builds rituals, solves anxieties, and provides symbolic resources for how we construct who we are in a consumer-driven world. in other words, branding doesn’t just create value for companies; it creates value for consumers navigating the identity marketplace.

what is value?

karl marx, in his classical theory, tells us value is primarily determined by the socially necessary labor time it takes to produce a commodity. he distinguishes between use value (the practical utility of something) and exchange value (its relative worth in the marketplace), and he adds the concept of surplus value, the profit extracted from workers when what they produce is worth more than what they’re paid.

but when we shift from the factory floor to the world of brands, marx’s definition feels a bit too narrow. modern critical scholarship pushes us to see value as a cultural and political construct that carries multiple meanings, depending on who is evaluating it.

think of boltanski and thévenot’s “worlds of worth”:

the market world measures value by price,

the civic world by contribution to the common good,

the green world by environmental sustainability,

the inspired world by creativity and passion,

…and so on.

these different value systems clash in branding. a brand can create value in one world (market growth, global recognition), while simultaneously destroying value in another (environmental harm, social exclusion).

the paper is guided by the question of

how may the value-destructive side of branding be brought into branding studies?

the answer, they argue, lies in shifting how we understand branding itself. not just as “distillation” (boiling down the essence of a company into a neat brand identity) or “platforming” (a co-creative space where companies and consumers build meaning together), but as discursive closure and hypocrisy.

branding as hypocrisy

bertilsson and rennstam also describe branding as hypocrisy. this happens when the brand’s official image is almost completely decoupled from its actual practices. the brand speaks one language, but acts in another. think of fast-food chains that advertise “healthy options” while still profiting primarily from burgers and sodas, or oil companies branding themselves as “green” while continuing to extract fossil fuels. hypocrisy, in this sense, is not an accident but a management strategy: it allows organizations to handle conflicting demands, maintain legitimacy, and deflect critique.

cphfw and its contradictions

this lens is particularly useful for analyzing cphfw today. while the event positions itself as the world’s most sustainable fashion week, it is simultaneously becoming more viral and popular through the very dynamics of influencer marketing - a system built on driving consumption. influencers, often invited and prioritized by brands, use cphfw as a stage for content that promotes trends, products, and aspirational lifestyles. this creates a contradiction: an event that speaks the language of sustainability is also amplifying the cycle of accelerated consumption, which undermines its own stated commitments.

moreover, this shift changes the hierarchy of the event itself. where designers and creativity once defined the core narrative, influencers now play an outsized role in shaping its visibility and symbolic value. the brand of cphfw, then, risks sliding into hypocrisy: projecting sustainability and inclusivity while reinforcing the same consumption-driven logics the industry claims to be moving beyond.

from copenhagen to havaianas

these dynamics extend beyond cphfw. consider havaianas: originally a brazilian working-class symbol, deeply embedded in everyday life and national identity. today, the brand is worn on european catwalks and summer streets as a fashion accessory, often stripped of its origins. many of the people wearing them have no idea of the cultural and social history behind the flip-flops; instead, they become another fragment in a global lifestyle narrative. this is branding at work: transforming cultural heritage into a marketable aesthetic, while silencing the histories, labor, and lived realities that gave it meaning.

value gained, value destroyed

thinking through boltanski and thévenot’s “worlds of worth” makes these contradictions clearer. cphfw gains value in the market world (through virality, brand sponsorships, and economic growth) and in the fame world (as its visibility spreads globally). but it risks destroying value in the green world (where sustainability is measured by genuine environmental practices, not marketing campaigns) and the civic world (where inclusivity means more than curated representation).

havaianas, too, gains in the fame world (becoming a global fashion item) and in the market world (selling at higher margins abroad). yet it loses in the domestic world, where its cultural and social roots in brazilian everyday life are erased, and in the civic world, where the broader story of class and identity tied to the brand is silenced.

in both cases, branding generates value for some worlds, while simultaneously destroying it in others. what remains is a polished narrative - sustainable fashion weeks, cosmopolitan flip-flops - that masks the contradictions underneath.

cphfw and havaianas remind us that branding is never neutral. it creates value, but it also silences, simplifies, and sometimes contradicts itself. the key is to ask: which worlds of value are being amplified, and which are being erased? only then can we understand branding not simply as progress, but also as a mechanism of closure that demands critique.

xx

ISSO TÁ DEMAIS!!! PALMAS

thanks for sharing with us a critical look at cphfw. a lot of the content out there focuses on the same aspects. to me, street style often gets even more attention than the fashion shows themselves. a really good point that also highlights consumerism.